During the 2018 Microsoft Hack Week, members of the Mono team explored the idea

of replacing the Mono’s code generation engine written in C with a code

generation engine written in C#.

In this blog post we describe our motivation, the interface between the native

Mono runtime and the managed compiler and how we implemented the new managed

compiler in C#.

Motivation

Mono’s runtime and JIT compiler are entirely written in C, a highly portable

language that has served the project well.

Yet, we feel jealous of our own users that get to write code in a high-level

language and enjoy the safety, the luxury and reap the benefits of writing code

in a high-level language, while the Mono runtime continues to be written in C.

We decided to explore whether we could make Mono’s compilation engine pluggable

and then plug a code generator written entirely in C#.

If this were to work, we could more easily prototype, write new optimizations

and make it simpler for developers to safely try changes in the JIT.

This idea has been explored by research projects like the

JikesRVM,

Maxime and

Graal for Java.

In the .NET world, the Unity team wrote an IL compiler to C++ compiler called

il2cpp.

They also experimented with a managed

JIT

recently.

In this blog post, we discuss the prototype that we built.

The code mentioned in this blog post can be found here:

https://github.com/lambdageek/mono/tree/mjit/mcs/class/Mono.Compiler

Interfacing with the Mono Runtime

The Mono runtime provides various services, just-in-time compilation, assembly

loading, an IO interface, thread management and debugging capabilities.

The code generation engine in Mono is called mini and is used both for static

compilation and just-in-time compilation.

Mono’s code generation has a number of dimensions:

- Code can be either interpreted, or compiled to native code

- When compiling to native code, this can be done just-in-time, or it can be batch compiled, also known as ahead-of-time compilation.

- Mono today has two code generators, the light and fast

mini JIT engine, and the heavy duty engine based on the LLVM optimizing compiler. These two are not really completely unaware of the other, Mono’s LLVM support reuses many parts of the mini engine.

This project started with a desire to make this division even more clear, and

to swap up the native code generation engine in ‘mini’ with one that could be

completely implemented in a .NET language.

In our prototype we used C#, but other languages like F# or IronPython could be used as well.

To move the JIT to the managed world, we introduced the ICompiler interface

which must be implemented by your compilation engine, and it is invoked on

demand when a specific method needs to be compiled.

This is the interface that you must implement:

interface ICompiler {

CompilationResult CompileMethod (IRuntimeInformation runtimeInfo,

MethodInfo methodInfo,

CompilationFlags flags,

out NativeCodeHandle nativeCode);

string Name { get; }

}

The CompileMethod () receives a IRuntimeInformation reference, which

provides services for the compiler as well as a MethodInfo that represents

the method to be compiled and it is expected to set the nativeCode parameter

to the generated code information.

The NativeCodeHandle merely represents the generated code address and its length.

This is the IRuntimeInformation definition, which shows the methods available

to the CompileMethod to perform its work:

interface IRuntimeInformation {

InstalledRuntimeCode InstallCompilationResult (CompilationResult result,

MethodInfo methodInfo,

NativeCodeHandle codeHandle);

object ExecuteInstalledMethod (InstalledRuntimeCode irc,

params object[] args);

ClassInfo GetClassInfoFor (string className);

MethodInfo GetMethodInfoFor (ClassInfo classInfo, string methodName);

FieldInfo GetFieldInfoForToken (MethodInfo mi, int token);

IntPtr ComputeFieldAddress (FieldInfo fi);

/// For a given array type, get the offset of the vector relative to the base address.

uint GetArrayBaseOffset(ClrType type);

}

We currently have one implementation of ICompiler, we call it the the “BigStep” compiler.

When wired up, this is what the process looks like when we compile a method with it:

The mini runtime can call into managed code via CompileMethod upon a

compilation request.

For the code generator to do its work, it needs to obtain some information

about the current environment.

This information is surfaced by the IRuntimeInformation interface.

Once the compilation is done, it will return a blob of native instructions to

the runtime.

The returned code is then “installed” in your application.

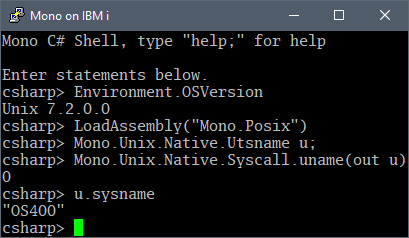

Now there is a trick question: Who is going to compile the compiler?

The compiler written in C# is initially executed with one of the built-in

engines (either the

interpreter,

or the JIT engine).

The BigStep Compiler

Our first ICompiler implementation is called the

BigStep

compiler.

This compiler was designed and implemented by a developer (Ming Zhou) not

affiliated with Mono Runtime Team.

It is a perfect showcase of how the work we presented through this project can

quickly enable a third-party to build their own compiler without much hassle

interacting with the runtime internals.

The BigStep compiler implements an IL to LLVM compiler.

This was convenient to build the proof of concept and ensure that the design

was sound, while delegating all the hard compilation work to the LLVM compiler

engine.

A lot can be said when it comes to the design and architecture of a compiler,

but our main point here is to emphasize how easy it can be, with what we have

just introduced to Mono runtime, to bridge IL code with a customized backend.

The IL code is streamed into to the compiler interface through an iterator,

with information such as op-code, index and parameters immediately available to

the user.

See below for more details about the prototype.

Hosted Compiler

Another beauty of moving parts of the runtime to the managed side is that we

can test the JIT compiler without recompiling the native runtime, so

essentially developing a normal C# application.

The InstallCompilationResult () can be used to register compiled method with

the runtime and the ExecuteInstalledMethod () are can be used to invoke a

method with the provided arguments.

Here is an example how this is used code:

public static int AddMethod (int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

[Test]

public void TestAddMethod ()

{

ClassInfo ci = runtimeInfo.GetClassInfoFor (typeof (ICompilerTests).AssemblyQualifiedName);

MethodInfo mi = runtimeInfo.GetMethodInfoFor (ci, "AddMethod");

NativeCodeHandle nativeCode;

CompilationResult result = compiler.CompileMethod (runtimeInfo, mi, CompilationFlags.None, out nativeCode);

InstalledRuntimeCode irc = runtimeInfo.InstallCompilationResult (result, mi, nativeCode);

int addition = (int) runtimeInfo.ExecuteInstalledMethod (irc, 1, 2);

Assert.AreEqual (addition, 3);

}

We can ask the host VM for the actual result, assuming it’s our gold standard:

int mjitResult = (int) runtimeInfo.ExecuteInstalledMethod (irc, 666, 1337);

int hostedResult = AddMethod (666, 1337);

Assert.AreEqual (mjitResult, hostedResult);

This eases development of a compiler tremendously.

We don’t need to eat our own dog food during debugging, but when we feel ready

we can flip a switch and use the compiler as our system compiler.

This is actually what happens if you run make -C mcs/class/Mono.Compiler run-test

in the mjit branch: We use this

API to test the managed compiler while running on the regular Mini JIT.

Native to Managed to Native: Wrapping Mini JIT into ICompiler

As part of this effort, we also wrapped Mono’s JIT in the ICompiler interface.

MiniCompiler calls back into native code and invokes the regular Mini JIT.

It works surprisingly well, however there is a caveat: Once back in the native

world, the Mini JIT doesn’t need to go through IRuntimeInformation and just

uses its old ways to retrieve runtime details.

Though, we can turn this into an incremental process now: We can identify those

parts, add them to IRuntimeInformation and change Mini JIT so that it uses

the new API.

Conclusion

We strongly believe in a long-term value of this project.

A code base in managed code is more approachable for developers and thus easier

to extend and maintain.

Even if we never see this work upstream, it helped us to better understand the

boundary between runtime and JIT compiler, and who knows, it might will help us

to integrate RyuJIT into Mono one day 😉

We should also note that IRuntimeInformation can be implemented by any other

.NET VM: Hello CoreCLR folks 👋

If you are curious about this project, ping us on our Gitter

channel.

Appendix: Converting Stack-Based OpCodes into Register Operations

Since the target language was LLVM IR, we had to build a translator that

converted the stack-based operations from IL into the register-based operations

of LLVM.

Since many potential target are register based, we decided to design a

framework to make it reusable of the part where we interpret the IL logic. To

this goal, we implemented an engine to turn the stack-based operations into the

register operations.

Consider the ADD operation in IL.

This operation pops two operands from the stack, performing addition and pushing back the result to the stack. This is documented in ECMA 335 as follows:

Stack Transition:

..., value1, value2 -> ..., result

The actual kind of addition that is performed depends on the types of the

values in the stack.

If the values are integers, the addition is an integer addition.

If the values are floating point values, then the operation is a floating point

addition.

To re-interpret this in a register-based semantics, we treat each pushed frame

in the stack as a different temporary value.

This means if a frame is popped out and a new one comes in, although it has the

same stack depth as the previous one, it’s a new temporary value.

Each temporary value is assigned a unique name.

Then an IL instruction can be unambiguously presented in a form using temporary names instead of stack changes.

For example, the ADD operation becomes

Temp3 := ADD Temp1 Temp2

Other than coming from the stack, there are other sources of data during

evaluation: local variables, arguments, constants and instruction offsets (used

for branching).

These sources are typed differently from the stack temporaries, so that the

downstream processor (to talk in a few) can properly map them into their

context.

A third problem that might be common among those target languages is the

jumping target for branching operations.

IL’s branching operation assumes an implicit target should the result be taken:

The next instruction.

But branching operations in LLVM IR must explicitly declare the targets for

both taken and not-taken paths.

To make this possible, the engine performs a pre-pass before the actual

execution, during which it gathers all the explicit and implicit targets.

In the actual execution, it will emit branching instructions with both targets.

As we mentioned earlier, the execution engine is a common layer that merely

translates the instruction to a more generic form.

It then sends out each instruction to IOperationProcessor, an interface that

performs actual translation.

Comparing to the instruction received from ICompiler, the presentation here,

OperationInfo, is much more consumable:

In addition to the op codes, it has an array of the input operands, and a result operand:

public class OperationInfo

{

... ...

internal IOperand[] Operands { get; set; }

internal TempOperand Result { get; set; }

... ...

}

There are several types of the operands: ArgumentOperand, LocalOperand,

ConstOperand, TempOperand, BranchTargetOperand, etc.

Note that the result, if it exists, is always a TempOperand.

The most important property on IOperand is its Name, which unambiguously

defines the source of data in the IL runtime.

If an operand with the same name comes in another operation, it unquestionably

tells us the very same data address is targeted again.

It’s paramount to the processor to accurately map each name to its own storage.

The processor handles each operand according to its type.

For example, if it’s an argument operand, we might consider retrieving the

value from the corresponding argument.

An x86 processor may map this to a register.

In the case of LLVM, we simply go to fetch it from a named value that is

pre-allocated at the beginning of method construction.

The resolution strategy is similar for other operands:

LocalOperand: fetch the value from pre-allocated addressConstOperand: use the const value carried by the operandBranchTargetOperand: use the index carried by the operand

Since the temp value uniquely represents an expression stack frame from CLR

runtime, it will be mapped to a register.

Luckily for us, LLVM allows infinite number of registers, so we simply name a

new one for each different temp operand.

If a temp operand is reused, however, the very same register must as well.

We use LLVMSharp binding to

communicate with LLVM.